Electricity Regulation in the Public Power State: Nebraska’s Electricity System and the Debate Between Public Ownership and Public Control

Commentary by Ryan McKeever

Ryan McKeever is from Nebraska and graduated from the University of Nebraska College of Law in 2024. He developed a passion for energy policy through his prior work experience at the United States Senate, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Ryan is currently an attorney in Minneapolis, Minnesota, working on renewable energy development for a national law firm.

Like all Commentary here on The Rural Review, this post expresses the personal opinions of the author.

The electricity industry in the United States is undergoing a period of massive and turbulent transition. These changes are driven by many factors including community response to climate change; increasingly frequent and damaging extreme weather events; technological advances in energy generation and distribution; and tremendous growth in energy usage from data centers, electric vehicles, and other sources. Communities are increasingly considering how to best structure their electricity systems to respond to these public concerns.

One recurring question around these issues is whether public regulation or public ownership can best serve public interest goals. Nearly every state has an agency with intensive regulatory powers to direct or influence the activities of electric utilities. However, even with state regulatory oversight, private utilities have faced persistent criticism, and public ownership of utilities is often touted as a potentially desirable alternative. In this debate about public ownership versus public regulation, Nebraska offers an interesting and underexamined case-study.

It is common knowledge among Nebraskans, and likely devoted energy policy nerds across the country, that Nebraska is the only state in the nation in which all electricity providers are publicly owned. However, Nebraska is also the only state without an intensive state regulatory regime for electricity. This article aims to bring Nebraska’s unique power system and electricity regulation regime into focus and set the stage for further research into the debate over the merits and drawbacks of ownership versus regulation of the electric power system.

The History of Public Power in Nebraska

Nebraska has a long history of public power stretching back to municipal electric systems that operated in the state in the 1880s. (Firth 1962, 9). However, Nebraska’s transition to 100% public ownership of utilities occurred primarily between 1933 and 1946. In the first part of the 20th century, Nebraska’s electric power system, like the rest of the country, was dominated by national utility holding companies. (Schaufelberger & Beck 2010, 37). By the 1930s, 80% of the electricity generated in the state came from these private, national utility companies. (Firth, 37).

Many economic, political, and social factors contributed to Nebraska’s transition to public power. The strength of populist political movements in the state and rural interest in “local control” likely played a part. However, federal legislation clearly spurred the transition. First, federal programs created in response to the Great Depression offered significant funding for public works, such as hydroelectric power and irrigation projects. In 1933, the Nebraska legislature passed the Enabling Act which provided for the creation of public power and irrigation districts as political subdivisions of the state that could apply for these federal funds. (Firth, 5). This enabled the creation of public entities that could compete with private utilities, and three major hydroelectric projects were built in the next decade by public power districts using federal resources. (Firth, 5).

Another major piece of federal legislation, the Public Utilities Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA), furthered the public power transition in Nebraska by weakening the private utilities. PUHCA required the breakup of the large private utility holding companies that had monopolized the electric power industry across the country. Public Power Districts in Nebraska, which were empowered by the Enabling Act to borrow money backed by revenue bonds, took the opportunity to purchase the assets of the soon-to-be broken-up private utilities. (Firth, 6).

Public power development was also furthered by Congress’s passage of the Rural Electrification Act in 1936, which provided financing for rural electricity projects. Dozens of “REA districts” were organized as either municipal, public power districts, or cooperatives organized as nonprofits, bringing electric power to farm and rural communities that private utilities had not served. (Firth, 6).

Public Power Districts across Nebraska. Source: Public Power in Nebraska, Nebraska Legislature

The public power transition was completed in 1946 when the only remaining private utility in the state, the Nebraska Power Company in Omaha, was purchased by the Omaha Public Power District. Nebraska’s entire private electric utility system was taken over by public entities in the span of just thirteen years. Since that day in 1946, all electric utilities in Nebraska have been publicly owned.

The Electric Power System in Nebraska Today

Ownership

The ownership structures and capabilities of Nebraska’s public power utilities vary. Electric utilities in the state are either municipalities, cooperatives, or public power districts. All public ownership entities share similar democratic leadership selection processes. Public power districts and cooperatives are run by elected boards, and municipal utilities are typically run by boards appointed by elected city councils. While all utilities share similar levels of local control, the different structures occupy different positions in the state’s electric system.

Most municipal utilities and cooperatives are small systems that do not generate any electricity of their own and instead purchase power from other entities and resell it to residents or members. (Nebraska Power Review Board, 16). However, some larger municipal utilities, including utilities in Lincoln and Grand Island, own their own generation assets. (Nebraska Power Review Board, 16).

Two large public power districts dominate the state’s electric power system: the Nebraska Public Power District (NPPD) and the Omaha Public Power District (OPPD). NPPD owns significant generation resources and is the largest wholesale seller of power in the state, selling electricity to 24 rural public power districts and cooperatives and over 100 municipalities. (Nebraska Power Review Board, 17). OPPD also owns significant generation resources and is the largest retail supplier in the state, serving thirteen counties in Eastern Nebraska. (Nebraska Power Review Board, 17).

Further, public power utilities are organized by other voluntary associations to achieve operational efficiencies, share reserves, and coordinate system stability. (Nebraska Power Review Board, 18). For example, over forty municipalities have joined together to form the Municipal Energy Agency of Nebraska which collectively secures power for all its member municipalities. However, the most notable association of public power utilities is the Nebraska Power Association (NPA). The NPA is an association of all 166 utilities that produce and deliver electricity across the state, and it acts as an industry forum and advocate for its members. The NPA has also been tasked by the Nebraska Power Review Board with completing statutorily mandated state power supply plans and transmission and energy conservation studies. (Nebraska Power Review Board, 33-34).

Nebraska’s Electricity Generation

Nebraska still primarily relies on burning coal for energy. Nearly half of the state’s electricity is produced by coal-fired power plants, and five of the ten largest generating power plants in the state are coal-fired. Wind energy provides about a third of the state’s total net energy generation. The rest of the state’s electricity comes primarily from nuclear or natural gas-fired power plants.

Source: EdWhiteImages via Pixabay

Nebraska Electric Power Regulation In Context

Nebraska’s electric power system is unique not only for its publicly owned utilities, but also for the hands-off approach the state takes in regulating the system. The Nebraska Power Review Board is the state regulator of electric utilities. However, the Power Review Board wields minimal power and is primarily a facilitator for resolving disputes among utilities. Instead, traditional state utility regulatory roles are generally left to the individual public power entities. Consider, for example, how Nebraska’s regulatory structure contrasts with the typical state utility regulatory regime regarding price setting, resource planning, energy facility, industry policy development, and regulatory procedure.

Retail Electricity Rates

The signature method of state utility regulation across the country is price setting. States grant utilities monopoly rights to serve certain areas, but in exchange, state regulators determine the rates a utility may charge its customers. Under the traditional state ratemaking formula, a utility may charge consumers rates that allow the utility to recoup reasonable expenses plus a percentage return on its investments. Regulators determine what utility expenses may be passed on to consumers, what rate of return utilities may recover on their investments, and how to design rates for residential, commercial, and industrial customers. (Davies et al. 2022, 276-299).

Typically, state statutes require that retail electricity rates be just, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory. (Davies et al. 2022, 276-299). Ratemaking, even when guided by these principles, involves challenging decisions about what expenses a utility should be able to pass on to consumers and what rate of return utilities should be able to earn on those investments. Additionally, regulators generally have wide discretion when determining what rate designs best balance difference aspects of the public interest. While state regulators seek to provide low rates for consumers and protect the financial health of utilities, they may also consider other public interest policy goals in designing rates. For example: Should prices be designed to encourage energy efficiency by charging increasing prices for higher levels of consumption? Should prices vary with the time of day and season to reflect the fluctuating prices that utilities pay for energy bought from wholesale markets? Should utilities be required to provide financial assistance programs for low-income ratepayers? Should utilities be able to offer special rates to businesses to encourage economic development? These are just some of the many complex considerations state regulators might weigh in designing the rate structures that utilities may charge consumers.

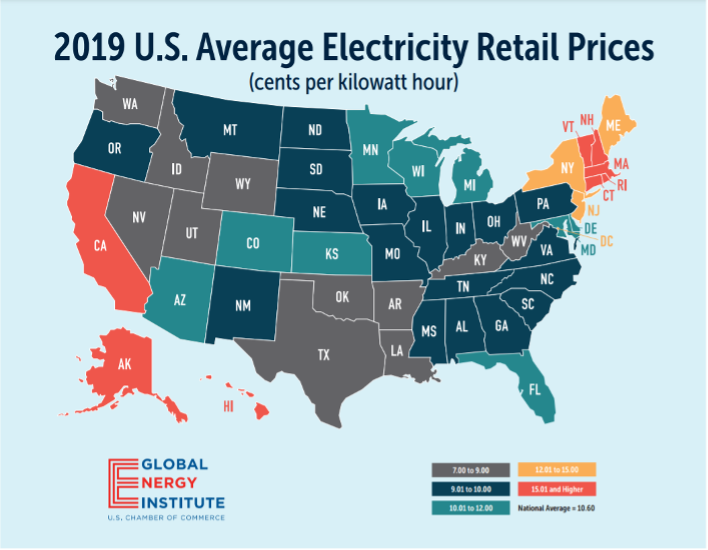

Summary of retail prices across the US. Source: MAP 2019 Average Electricity Retail Prices, U.S. Chamber of Commerce Global Energy Institute

Nebraska, on the other hand, is the only state where no state agency approves retail electricity rates. (Nebraska Power Review Board, 7). Instead, rate decisions are made by each individual public power utility, restricted only by the statutory standard that rates must be “fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory”. Each public power utility in Nebraska also has broad flexibility to structure rates to balance aspects of the public interest.

Resource Planning

In addition to regulating the cost of electricity, state regulators also often regulate the type of generation resources in which utilities invest. Many states require utilities to undergo intensive resource planning processes in which utilities forecast their future energy demand and create plans to meet that demand. States typically require utilities to submit these plans for state review and approval. Further, most states also impose Renewable Portfolio Standards or Clean Energy Standards that require a certain percentage of electricity come from renewable or carbon free energy sources. (Davies et al., 465-469). In many states, regulators use their resource planning powers to require utilities to invest in certain energy sources or decommission existing energy sources in order to improve system reliability, reduce harmful emissions from energy production, or pursue other public interest goals.

In Nebraska, no state agency or law controls public power utility resource planning. Public utilities are required by statute to practice integrated resource planning, meaning that plans must consider the full range of energy supply and demand options, including energy efficiency, conservation, and renewable resources, among other things. However, neither the Nebraska Power Review Board, nor any other state regulator has any power to deny or require amendments to the plans. In addition to submitting these resource plans, in Nebraska a representative of the Public Power Districts must also file a statewide coordinated long-range power supply plan and an annual load and capacity report with the Power Review Board. NPA, as the representative of the state’s Public Power Districts, files these reports as required by statute. (Nebraska Power Review Board, 32). While the reports must be filed with the Power Review Board, the Board has no power to deny or require amendments to the reports.

Additionally, Nebraska does not have a statewide Renewable Portfolio Standard or Clean Energy Standard. However, as with other areas of energy law in Nebraska, the power to make these resource planning decisions is delegated to the individual utilities. In fact, the three largest utilities in the state—NPPD, OPPD, and the Lincoln municipal electric system—have all adopted goals of achieving net-zero emissions from their generation resources.

Other Energy Policies

State regulators also have power to dictate other utility standards, practices, and policies. State regulators often do so to correct for market failures that result from the monopoly structure of retail electricity delivery. For example, because an electric utility is a monopoly with captive consumers, it is financially incentivized to maximize sales to increase revenue. This incentive may conflict with public interest goals of increasing energy efficiency. So, in response, many states have adopted standards and policies to compensate utilities and ratepayers for energy efficiency upgrades. Further, many states have also developed policies to compensate consumers who reduce the amount of energy they draw from the grid. Some states have adopted programs to compensate ratepayers for home energy efficiency upgrades. Other states go even further. For example, some states require utilities to pay consumers, or at least offset consumer energy bills, for energy produced by solar panels on a consumer’s rooftop or for energy demand avoided by “demand response” technologies such as smart thermostats or water heaters that adjust energy consumption during certain time periods. In many states, regulators take active roles in considering rules to ensure the electric power systems operates in the public interest.

In Nebraska, state regulators do not have power to direct utilities to abide by any energy policy priorities. Instead, utilities are generally free to govern their own affairs. Under the direction of its elected or publicly selected leadership, each public power utility in Nebraska operates with its own unique standards, practices, and policies.

Procedural Elements of State Energy Regulation

In addition to the substantive differences between Nebraska’s energy regulatory regime and the typical state system, there are also significant procedural differences. Typically, other states handle all these regulatory matters through notice-and-comment rulemaking and quasi-judicial public proceedings. Under the notice-and-comment process, regulators must publish their proposed regulations to notify the public and give them an opportunity to submit comments. Regulators then consider and respond to public comments before issuing a final regulation. To enforce its regulations, state utility regulators typically use a quasi-judicial process. A utility will file proposed rates, plans, or policies to abide with certain regulations, the public may comment on the utility’s proposal, and then the state regulator will ultimately review the utility filing and all public comments to determine whether the proposal serves the public interest or must be revised. Public input in any given proceeding could include comments from citizens, industrial or commercial consumers, energy and environmental nonprofits or advocacy groups, or other local or federal government agencies. Additionally, states often task other state agencies or public officers with the responsibility to engage in these public proceedings to articulate state energy policy priorities, advocate on behalf of consumers, or otherwise promote the public interest.

Utilities in Nebraska generally are not beholden to a similar adversarial adjudication process. Nebraska’s Public Power Districts are required to make decisions during public meetings in which citizens may participate. However, utilities are not required to consider and respond to public comments regarding its decisions. Further, no public officer or agency is tasked with advocating in utility decision-making.

It should be noted that Nebraska’s lack of intensive procedural regulations for publicly owned utilities is not novel. Many other states exempt municipal, cooperative, and other public or nonprofit utilities from their retail electricity regulations. However, with a few exceptions, public power exemptions in other states likely only affect a small portion of the given state’s electric system; publicly owned utilities serve just one-seventh of electric power customers across the country. But in Nebraska, the public power exemption and the lack of a traditional state regulator effectively delegates all electric regulatory powers to the various individual public entities.

Further Research Based on the Nebraska Model of Electric Power Regulation

Nebraska’s unique legal framework provides an interesting case study for considering how to best structure energy systems to serve public interest goals. In Nebraska, public ownership effectively translates to regulation by a more localized governmental entity instead of a statewide regulatory agency. More research could be done to publicly compile and compare how each public power utility handles ratemaking, resource planning, energy policies, and decision-making processes. By comparing Nebraska’s utilities to each other and to utilities in other states, this could provide a basis for considering how local control could better serve certain public interest goals. Beyond Nebraska, more research could be done to consider the lessons Nebraska’s system demonstrates about the opportunities and limitations of public ownership. I offer three categories of research inquiry for consideration.

Public Regulation versus Public Ownership. In what ways do public utilities in Nebraska and private utilities heavily regulated in other states operate similarly or differently? For example, how does ownership structure affect a utility’s decision to develop generation resources under their own auspices as opposed to purchasing energy from third party producers? How do the different systems, Nebraska’s model or the traditional utility regulation model, raise and consider different aspects of the public interest? What is gained or lost by Nebraska’s lack of quasi-judicial regulatory proceedings with input from interested parties and state regulators? Does the smaller size of public utilities in Nebraska affect the utility’s technical capacity or sophistication compared to private utilities beholden to a statewide regulator in other states? What is gained and lost by decisions made by state regulators at the statewide scale, compared to those made at the local scale in Nebraska?

Economic and Environmental Justice. Does the public control of utilities deliver economic benefits to citizens and consumers compared to the for-profit, private utility model? Are rates and rate designs calibrated to affect the public interest in different ways in Nebraska than in other states? Also, as private utilities are often major state-level political and lobbying actors, how do the political and lobbying actions of public power utilities in Nebraska compare to those of private utilities in other states? Does public ownership of utilities improve their record on environmental stewardship?

Clean Energy Transition. How has Nebraska’s public power model advanced or limited the state’s adoption of clean energy? In what ways can public ownership of utilities advance renewable energy deployment, and in what ways might public ownership hinder it? How will local economic reliance on fossil fuel generation affect public power utilities’ decision-making on decommissioning fossil fuel plants? How does local support for, or local opposition to, renewable energy siting affect renewable energy deployment in public power utilities versus private utilities?

Conclusion

The optimal structure and operation of the nation’s electricity system is a subject of serious public concern. Further research into Nebraska’s unique public power system along these lines may be able to help Nebraskans consider how to improve their own system and may help communities in other states better evaluate the challenges and opportunities of public ownership of utilities.

Continue the Conversation! The Rural Reconciliation Project welcomes similar contributions from a range of rural and non-rural voices here on The Rural Review.

Find our submission guidelines here.